Encounters With Wild Animals In The Arctic

Polar Bear

While serving in the Canadian Coast Guard as Telecom Officer on the CCGS Labrador, we spent the summer of 1965 in the high arctic, surveying for the Hydrographic Service of Canada. At the early part of our voyage, we anchored in Diana Bay, which was an inlet for Ungava Bay. One bright summer day, we noticed a large polar bear on the shore. As we watched we were amazed that he jumped in the water and swam out to our ship.

Perhaps he had poor eyesight or perhaps he just didn't give a damn, but he wasn't afraid of our ship at all. As he swam the several miles out to our ship in the very calm water, his nose made a long V in the water which stretched for miles. Everyone who could got their cameras and snapped photos of him as he dauntlessly swam around our ship a couple of times, then swam back to shore.

It was a beautiful experience but I certainly would not like to come any closer to a Polar Bear in the wild.

Arctic Wolf

One day, during the winter, I decided to go ice-fishing at the lake in back of our Dew Line Site. It was a beautiful clear day, so I looked forward to cutting a hole in the ice, and catching some of the Dolley Varden trout that inhabited the lake. This time of year, they were in breeding colours, and were very colourful.

As I walked deep in thought over the crest of a knoll, I almost bumped into a wolf coming straight towards me. As I suddenly saw him, my mind had not registered yet, and I immediately thought - What is a dirty sheep doing up here in the high Arctic? Then it hit, me- A WOLF!

I don't really know which one of us was the more surprised. He immediately sprung backwards and started running away down the slope, over the frozen lake, and up a distant hillside. As for me, I straddled the ground and pulled out my binoculars and watched him retreat. He would run for a hundred feet or so, and then stop to look back at me. He kept that rhythm up until he was out of sight over the far range of hills. I felt that this experience was very special; How many people can relate to an incident when a free wild Arctic Wolf shares such a moment in time? Two beings from different worlds, that would forever go their separate ways, but for one fleeting moment, we both experienced the mutual surprise of nearly bumping into each other alone in the Arctic on a cold winter's day.

The one pack of Wolves that lived in our area, never bothered anyone. They had their cubs every Spring, and sometimes visited our garbage dump for easy food. One day, the local Eskimos decided to kill them and tried to sell us the pelts. To a man, we refused to have anything to do with this slaughter, and they got nothing from us. I think they got the point.

What is that nibbling at my parka?

One day, I was looking for some gear so I drove down to our airstrip, six miles from the site. As I drove up to a locked shed, I looked around the landscape to ensure there were no wild animals., especially Polar Bears in the vicinity.

I got out of the truck and went over to the shed where the door was locked. I had a ring of keys, and one of them would fit the lock so I bent forward and meticulously tried each key in turn. After about ten minutes of trying these keys, I suddenly felt a scratching at the rear of my parka. I froze in fear. what was it? What animal was scratching at me? Was it a Polar Bear? There was no noise, and it scratched my parka again. I realized if it was a Polar Bear, I would be lucky if it killed me right away. I still had no idea which of these many keys on the ring would fit the lock on the door so I was stuck outside with whatever animal it was that was interested in my parka - or maybe me.

I had no choice, one way or the other, I had to turn around and see what it was. Slowly, I turned around and saw what creature was interested in me. To my immense relief, it was a barren ground Caribou, the Caribou with the largest antlers in the world! He was merely curious, and I was so relieved I searched my pockets for something to give him to eat. I think that experience was the closest I ever came to having a heart attack through fear.

Later that Autumn, I found myself on the frozen Baird peninsula running amongst a heard of over a thousand migrating Caribou, taking pictures for the guys back at the site. I remember seeing several large males in a group whose antlers were so large, that I couldn't see their bodies as they were eating, just their antlers over the rise. These guys were magnificent but it sure wasn't hard to get up close to one.

Barren

ground Caribou

Arctic Char

We white people were not allowed to fish hunt or to set up nets on Dew line sites. Only the Eskimos were allowed to do those things. Nevertheless, a fellow from Winnipeg and I decided to set up a net like they do on the Bay of Fundy where I grew up. We ordered two nets from the Hudson's Bay Company in an Eskimo's name, and it was delivered by mail about a month later. I sewed the two nets together to make a total length of fifty feet. It was a two inch mesh which was standard for netting normal size fish such as Arctic Char and Dolly Varden trout.

Every day one of us had to check the net at low tide and ensure all the netted fish were removed, or the Sea lice would go inside the fish and eat them from the inside out rendering them inedible. We caught enough fresh fish that summer to fill the station's freezer.

One day, I decided to walk down to a point of land where the Piling river meets the sea, and try my hand at casting out into the ocean. I found that I could only cast the lure out about twenty feet. This certainly was not the type of casting I was used to, and I quickly became disillusioned with this casting gear. Despite this inadequacy, I cast out several times in hope that I might snag something. On the fourth cast, I felt a strong tug, and I immediately went into my fishing mode.

I was delighted it felt like a large fish, and I successfully brought him ashore. I was so thrilled at this catch, I abandoned any further fishing attempts and proudly carried it back to the site. It weighed 12 1/2 pounds on the scale. That was the one and only time I ever fished on the Arctic ocean. So you could say I have a perfect record fishing there.

The Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) has the most northerly distribution of any freshwater fish. It is the dominant species of the Arctic coast, and for centuries has been an important food resource of the Inuit.

Arctic Fox

A couple of Arctic Foxes came by the site one day in the winter. They acted quite friendly so we decided to try and tempt one into a module. With a fishing line and some meat for bait, we successfully suckered one in. Here is a photo of him sitting under a chair rather uncomfortable due to the inside warmth that we humans take for granted. We took some photos and then let him back outside, where I am sure he was much more comfortable.

Red Fox

Yes, we had a resident Red Fox at our site. I later researched them, and they have successfully established themselves up into the lower Arctic, although not as widely spread up there as is the smaller Arctic Fox. Our red had quite a home range, and he must have always been on the lookout for the much larger wolves who dominated the food chain thereabouts.

Walrus

During a return flight after my R & R leave down south, the pilot decided to lower the DC4 to much lower than usual so we could get a good look at the thousands of Walrus sunning themselves in the short summer sun between Baffin Island and Rowley Island going west. It was an experience I'll never forget.

As we flew low over the ocean at low level, the Walrus herds did not see us until we were almost over them. As they suddenly became aware of us overhead, they immediately plunged into the frigid water en mass. It was a marvelous sight with all those mighty animals beneath us. It was something that is not possible without the willing cooperation of the pilot.

Arctic Hare

Back in northern Ontario and the Maritimes, I had hunted the only rabbit species that was available there, the Varying Hare. Naturally I was curious just how the Inuit (In the 1960s, we referred to them as Eskimos) hunted the Arctic Hare. So one day I asked Abraham Kaunak if I could follow him on a Hare hunt. It was mid Spring, but there was plenty of snow still around. Abraham used a .22 calibre rifle similar to what I had used.

As we trudged across the tundra, I soon fell well behind him. With my heavy white man's winter garb, I could not keep up with him. Of course, his clothing was lighter and more practical than mine. Soon, he came across some Hare footprints in the snow. He immediately followed them looking as far ahead as he could see in the line of tracks. After about 20 minutes he encountered the Hare sitting up about 20 feet away amongst some rock outcroppings, and looking directly at him.

Abraham aimed the rifle and fired. The bullet missed entirely. The Hare merely sat there patiently while Abraham selected a small rock and hit the front sight towards the left. He aimed and fired again. Missed again. The Hare still maintained his sitting posture probably wondering what this human was doing making such a loud cracking noise with nothing resulting from it. The Arctic Hare are much larger than our southern Varying Hare, and they have a peculiar habit of running on their hind legs when they are startled.

Abraham said nothing, and adjusted the front sight several times first in one direction, then the other with that rock until finally he managed to hit the rabbit. I was not impressed. Back home, I would have sighted the rifle in before I left on a hunt. However, I guess he knew the Hare would not run away. As with most animals in the area, it was completely unaware of the danger posed by humans. The only animals I saw that were afraid of us were the wolves, and probably with good reason.

I never went hunting with an Eskimo again as I was now satisfied I knew how they hunted Hares up here.

The Canadian Federal Department of Northern Affairs had directed all DEW Line managers to feed the Inuit on site less meat than they actually needed to survive so as to give them an impetus to occasionally hunt. Of course, all the Station Chiefs ignored that directive as they felt it was supremely idiotic. The government reasoning was that they did not want the Inuit to lose their ability to hunt, as the DEW Line would not be around forever. And sure thing, it closed down in the 1970s, leaving those Inuit who had worked on it for so many years, unemployed. So maybe it as not a bad idea after all.

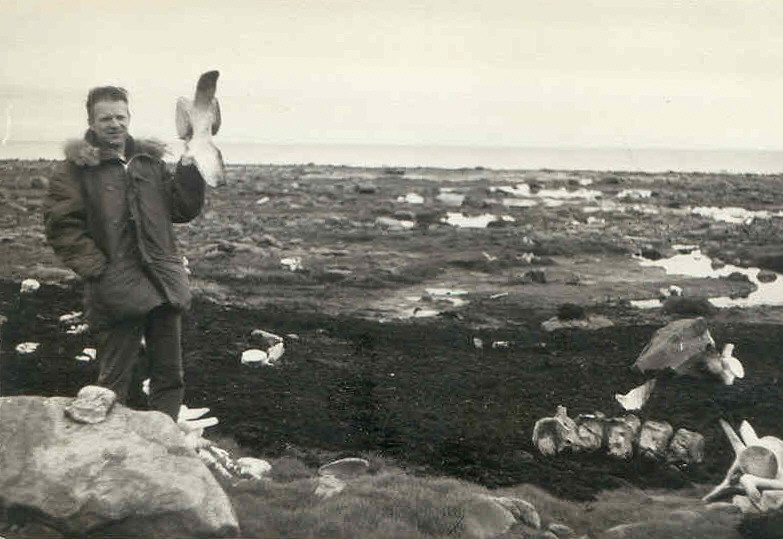

Whale (bones)

It didn't take much to notice the huge whale skeleton down on the beach. How long it had been there or why it was there at all, was all conjecture. No one knew what kind of a whale it was, and no one seemed to care. Anyway, there was a thick black substance where the whale's body fluids had drained onto the sand, and hardened. The backbone was the largest feature.

We all were stunned by the size and mere presence of this great creature. It demanded a certain respect in all of us, and it reminded us that we are all mortal beings. We realized that as temporary beings, some day, each of us would have our bones placed somewhere but they would never be as significant as this.

Scientists have recently determined some polar whale species live well over 200 years making them the longest lived of any mammal species. One could not help but wonder what kind of a life this magnificent creature experienced. Did it witness Frobisher, Hudson, and other Arctic explorers or did it even remember stone age man throwing stone tipped spears at it? We all considered this site with a certain reverence, and none of us asked for the bones to be buried. We all felt it was best to just let nature take its course.

Local scavengers, including wolves, foxes, polar bears, ravens and sea lice had a boon for months, maybe years, as they slowly devoured this prize. It would take much longer to decay up here in this cold environment than it would have if the creature had washed up on a beach in a more temperate climate. Nevertheless, gradually, all the bones would eventually turn to powder, and no one would ever realize what monumental event had occurred here.

Here I am holding up a backbone joint.

Raven

It was an unlikely area in the world to expect a solitary Raven to crackle and warble day and night. Although day and night blended into one. During the summer months, it never got dark. During the winter months, it was always dark,. not a pitch dark, but not daylight either. Nevertheless, there he was talking his own Raven talk to himself mostly. He usually perched on the topmost area of one of the four Tropospheric scatter antennas, secure in this high man-made structure, for there were no trees hereabouts.

He was comforting in a way. It was rather pleasant to have a familiar bird in the vicinity. Odd though, since his shiny black feathers seemed a bit out of place in the snow covered Arctic. I figured nature knew what she was doing in making the Raven black. The feeble sun's rays would warm up his dark body much more than if he were snow white like most other animals up here.

They say a Raven can mimic any other animal he listens to. Down south, I sometimes heard a Raven in the woods mimic other animals such as a barking dog or a quacking duck. But up here, I didn't recognize his effusive sound bits at all. They seemed to consist merely of cracking sounds. I guess they might have been pure Raven-inspired. Anyway, he was there when I arrived, and he was still there a year later, when I left, so perhaps he is still there.

I once read in a book that Ravens live for about 75 years, and that they are exceptionally intelligent. What I couldn't figure out was why was he way up here in this "hard-to-find-food", very cold place. I finally gave up trying to figure him out. God, he talked a lot, especially when I was trying to get some sleep..

As you can see, the Arctic is not a "desolate wilderness" as it is often described. In the short summer, the valleys abound with beautiful wild flowers, and the lakes and marshes are full of nesting water birds, ranging from huge white swans to Canada & Snow geese to the tiny Arctic Terns.

Let us hope the fragile ecosystem in Canada's Arctic remains pristine and unchanging forever.

My year on the DEW Line was difficult in that I was away from my young family. However, it was a unique and cherished experience that will stay with me the rest of my life.

Hal MacGregor, Author and Researcher.

The author at age 25 on the DEW Line